Flights begin and end in the traffic pattern. Unfortunately, many accidents happen there, too. As a general aviation pilot, it behooves you to not only practice takeoffs and landings but also pattern departures and entries, paying careful attention to altitudes, airspeeds, and procedures.

Spending extra time learning the airport-specific arrival and departure procedures for your home field goes a long way. For example, your airport may have published noise abatement procedures — which call for pilots to reduce engine power after reaching a certain altitude — but another airport may not require them. Know before you go.

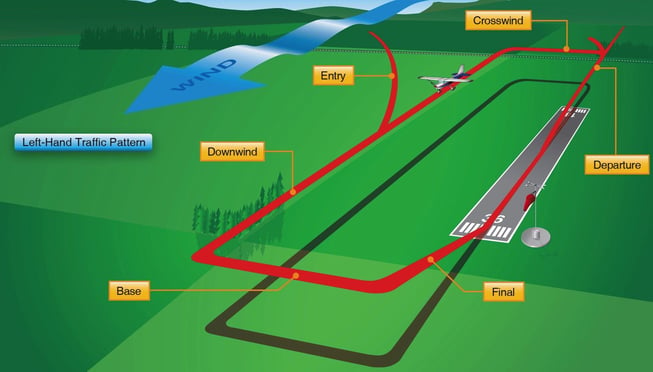

A standard traffic pattern has five parts, the so-called “five legs.” For each one, there a few important things you should remember.

Upwind Leg

The first leg is upwind, also known as the climb out, which takes the airplane from the ground to the traffic pattern altitude.

You should climb at Vy, your best rate of climb speed, unless there is an obstacle ahead. In that case, you should climb at Vx, your best angle of climb speed, until the obstacle is cleared. Then, you should accelerate to Vy.

During the climb on upwind, you should maintain a ground track consistent with the runway heading. Please do not be that person who looks over his shoulder to see if he is still lined up on the centerline, turns his whole body (including hands on the yoke), and inadvertently applies rudder in the direction he is looking. Instead, as you lift off, spot something off the extended centerline in front of the airplane and aim for it.

Related Content: Pilot Proficiency: You Still Have the Controls

Crosswind Leg

After upwind, the next leg is crosswind, which is perpendicular to the runway by 90 degrees.

You should turn crosswind when the aircraft is approximately 300 feet below pattern altitude unless locally published procedures specify differently. Always look in the direction of the turn and verify all is clear before making it. If another aircraft is approaching the pattern, turn behind it.

Your bank angle in the pattern should not exceed 30 degrees. A steeper bank angle results in a faster turn, which results in a faster pattern. That gives you less time to configure (i.e. stay ahead of) the airplane.

When the aircraft reaches pattern altitude, put the nose on the horizon, allow it to get to pattern speed, adjust the pitch and power, and trim for level flight.

Position the aircraft where the runway is approximately a half mile to one mile off the wingtip. Unless you are going to ask it for a date, try not to fixate on the runway. When most pilots fixate, they tend to fly into the runway.

Downwind Leg

On the downwind, run the pre-landing checklist: gas on both or best tank, undercarriage down, mixture rich, fuel pump, propeller (if applicable or deferred), and safety items such as seatbelts and lights on.

Adjust the power to reach the speed recommended in the pilot's operating handbook (POH) for the aircraft — 90 knots, for example.

Be aware of traffic approaching on the 45° and aircraft overflying the airport to enter the pattern.

When the aircraft is abeam the intended point of touch down, reduce power to slow it to flap deployment speed. Verify the speed is within the white arc. Then, drop the first notch of flaps and trim for the appropriate speed. The aircraft should start to descend.

Try to avoid deploying flaps during a turn; this can result in asymmetrical flaps (when one side comes down more than another). Asymmetrical flaps can lead to an uncommanded roll and stall. In the pattern, you do not have the altitude for recovery.

Continue on the downwind until the runway is 45 degrees to the aircraft, and then initiate the base turn. Between the power reduction and the base turn, the aircraft should lose about 200 feet.

Base Leg

On the base leg, you should evaluate the need for a power adjustment and more flaps.

The turn from base to final should be a coordinated, standard rate turn. Time it just as you would throwing a football to a person running for a pass, adjusting the bank angle to make the aircraft roll wings level as it comes out on centerline.

Final Approach Leg

On final, you should note the glide slope indications.

- Red over red — bump your head, add some power, or we'll all end up dead.

- White over white — we'll be up here all night.

If all is good, reduce the power and add another notch of flaps. Focus on an aiming point on the runway, such as the numbers. Run the pre-landing GUMPS checklist every time you make a turn.

Once established on final, adjust the power and add flaps if necessary to come down faster without an increase in airspeed. You want to make sure the aircraft is stabilized.

Some flight instructors teach that you should always use full flaps, and others ask the pilot to identify and recognize the need for flaps in every situation. Some pilots prefer not to use more flaps than they would during a go-around, instead preferring to manage the approach with pitch and speed.

Aim to land on the first third of the runway, and get the aircraft to touch down and stop as soon as possible (unless otherwise directed by the air traffic control tower). Do not slam on the brakes. It is much better to control your airspeed on approach in order to land at the speed specified in the POH.

As you transition from flying to landing, bring the nose of the aircraft up about an inch when it gets over the runway. Hold that attitude, the nose up as you verify the approach speed on the airspeed indicator, and keep one hand on the throttle. Let the runway come to you.

You do not need to slam the nose down. Hold the back pressure until the airplane quits flying and the nosewheel touches down on its own.

Related Content: 3 Great Approaches to Get Your Blood Pumping

Keep In Mind

Every turn is 90 degrees in relation to the heading of the previous leg. So, if you are taking off from runway 35 and using left traffic, the crosswind turn will be to a heading of 260°, the turn to downwind will be to a heading of 170°, and the base turn will be to a heading of 080°.

Radio calls in the traffic pattern

On takeoff, if you are staying in the pattern, specify that you are “taking off runway (insert number), remaining in the pattern." The phrase "departing the runway" gives the impression you are leaving the pattern, which can confuse other pilots.

If you do intend to leave the pattern, be specific:

- "Departing the pattern to the south, via the crosswind"

- "Straight out departure"

If it is a named procedure, add that detail.

- "via the Green Field departure.”

Call your turns (per the Aeronautical Information Manual [AIM]), and be sure to indicate a touch-and-go or a full stop.

Departing the traffic pattern

Chapter four of the AIM tells us to depart on the crosswind. The AIM is not regulatory, but it is good operating practice. If your airport has specific VFR departure procedures, learn them and fly them as published.

Although many people do it, climbing while departing on the downwind can be dangerous. The aircraft climbing could run into an aircraft overflying the airport at 500 feet above pattern altitude in order to enter the pattern on the 45°.

Instead, for your departure, remain at pattern altitude until you are slightly past the position where you typically would turn crosswind. Then, turn and start your climb to altitude.

Entering the traffic pattern

When approaching the airport, be it controlled or uncontrolled, listen to the ATIS/ASOS/AWOS to get the weather and determine which runway is in use.

If able, always land into the wind. There may be a time when the winds have shifted, and the other pilots in the pattern or the tower may advise the runway is about to "switch.” So, although people have been taking off and landing on runway 17, it's time to move operations to runway 35. Be gracious about this, and enter the pattern on the 45.

To position yourself for the 45, overfly the pattern at an altitude 500 feet above the published pattern altitude. Look out for any pilot climbing out on downwind.

Enter the pattern on a 45° to arrive at the midfield point of the downwind.

Practicing pattern procedures

An airport traffic pattern is a busy place, which makes it a horrible classroom. It may behoove you to get your flight instructor to go into the practice area and practice the pattern procedures at altitude using the cardinal heads for the legs. Begin at an altitude that allows you to "land" at an altitude of at least 1,500 feet AGL.

-1.png)